Osman I: The Founder of the Ottoman Empire

From a small principality in Bithynia, Osman I’s leadership and victories against the Byzantine Empire paved the way for the rise of one of history's greatest empires.

Osman I, also known as Osman Gazi (c. 1258 – c. 1323 CE), was the founder and first Sultan of the Ottoman Beylik, which would rise to eventually become the Ottoman Empire. He was the ruler of a small Turkic principality among many in the Anatolian region of Bithynia and, through a series of victories against the Byzantine Empire, would lay the foundation for his ancestors to build an empire spanning three continents, lasting centuries, and leaving its influence on the Middle East, Balkans, and the world.

Geopolitical Background

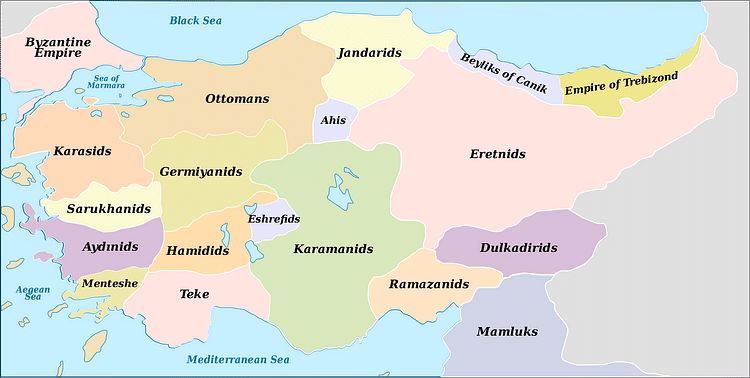

On 26 August 1071 CE, the Byzantine Empire was defeated by the Seljuk Turks under the command of Alp Arslan at the Battle of Manzikert. The defeat was a major strategic loss for the Byzantines in Anatolia, which opened the gates for its eventual conquest and colonization. The Seljuks were a confederation of ethnic Oghuz Turkic tribes, a nomadic people tracing their origins to the steppes of Central Asia and who had converted to Islam. The Seljuks had considerable success in Anatolia and the Middle East in the years following Manzikert, however, due to internal power struggles, conflicts with crusaders, and the emergence of the Mongol Ilkhanate, the Seljuks in Anatolia rebranded first into the Sultanate of Rum in 1081 CE and then fractured into several principalities known as Beyliks. And among those many Beyliks, was Osman’s domain.

Life & Rise to Power

Information about Osman’s early life is scarce. Outside of contemporary Byzantine accounts of his battles with their forces, records of his life were, for the most part, written posthumously at the behest of Ottoman sultans centuries later.

Osman was born circa 1258 CE in the city of Söğüt located in the northwestern Anatolian region of Bithynia. His father was Ertuğrul, a chieftain from the Kayı tribe under the command of the Seljuks. He was rewarded pasturing lands in Bithynia by the Sultan of the Seljuks for his tribe’s distinguished service.

In his youth, Osman married Malhun, the daughter of Sheikh Edebali a prominent local Sufi cleric and close confidant of his late father. Edebali himself was initially reluctant to give his daughter’s hand in marriage to Osman, however, he changed his mind after hearing Osman recount what he believed was a prophesizing dream. In this mythological dream, he saw a moon rise then dip into Edebali’s chest with a tree sprouting from it and providing people with shade and streams of water. Edebali believed this prophesized Osman’s prosperous future empire. Scholar of Ottoman studies Caroline Finkel emphasizes:

First communicated in this form in the later fifteenth century, a century and a half after Osman’s death in about 1323 CE, this dream became one of the most resilient founding myths of the empire, conjuring up a sense of temporal and divine authority and justifying the visible success of Osman and his descendants at the expense of their competitors for territory and power in the Balkans, Anatolia, and beyond. (32)

Conquests as Ruler of the Ottoman Beylik

Following the death of his father Ertuğrul c. 1280 CE, Osman took command of the tribe and organized his forces for conflict with the Byzantines. His first order of business was to establish three Uç Bey (frontier commanders). The Uç Bey were each responsible for a border district and were in charge of rallying light-cavalry raiders to fight enemy forces before the regular army engaged them. Later into Ottoman military history, these irregular troops would evolve to be known as Akinci, and were not paid by the state but were rather compensated by whatever they could loot in enemy territories.

Osman’s Uç Bey were established facing three fronts. One towards the Byzantine stronghold of Nicomedia, one towards Nicaea, and last facing the Black Sea. Relying on the cavalry-centric military tactics of his Central Asian ancestors, Osman’s forces began their conquests by capturing small settlements in the countryside, furthering their foothold in Bithynia. Among these settlements were Eskişehir and Yenişehir, with the latter becoming the first formal capital.

During this time, Osman turned his attention north towards one of the biggest prizes of the region, the city of Nicaea. The city of Nicaea (modern-day İznik) fortified with a city wall, and protected by a large garrison was an important Byzantine administrative center and one of the few cities that had not been occupied by crusader forces during the Fourth Crusade launched by Pope Innocent III in 1198 CE. A century later in 1299 CE Osman’s forces laid siege to the city. However, Nicaea would prove to be too formidable of a target as the siege ended in defeat two years later.

Although Osman was ultimately unsuccessful in his bid to take Nicaea, c. 1302 CE his exploits caught the attention of the Byzantine emperor Andronicus II Palaeologus. In an attempt to court the Ilkhanids to take action against Osman, Palaeologus offered a political marriage with a Byzantine princess to their khan. The khan died before being able to keep his promise, so Palaeologus hired Catalan mercenaries in their stead. They would ultimately defect, leaving the emperor to seek the aid of the Kingdom of Serbia.

Siege of Prusa & Death

Byzantine hegemony in Bithynia further evaporated in 1302 CE when Osman and his forces defeated the Byzantines at the Battle of Bapheus near the Sea of Marmara. The outcome of the battle allowed Osman to consolidate his hold on the countryside leaving many major Byzantine cities within striking distance. In the following years, Osman would regroup in Yenişehir, and continue absorbing small settlements into his fledgling principality. Eventually, in 1308 CE, he completely isolated the Bithynian capital of Prusa (modern-day Bursa) and lay siege to it. The defenders held out valiantly thanks to a steady stream of supplies and reinforcements through their maritime connection with Constantinople. The situation remained a stalemate for over a decade until 1321 CE when the last port supplying Prusa was captured by Osman’s forces. Osman, however, would not see the siege to completion. He died c. 1323 CE and his son Orhan would be the one to capture the city. Orhan succeeded his father as Bey and further expanded the territory he inherited. Going on to almost fully annex the region of Bithynia and arrive at the gates of Constantinople.

Domestic Affairs & Legacy

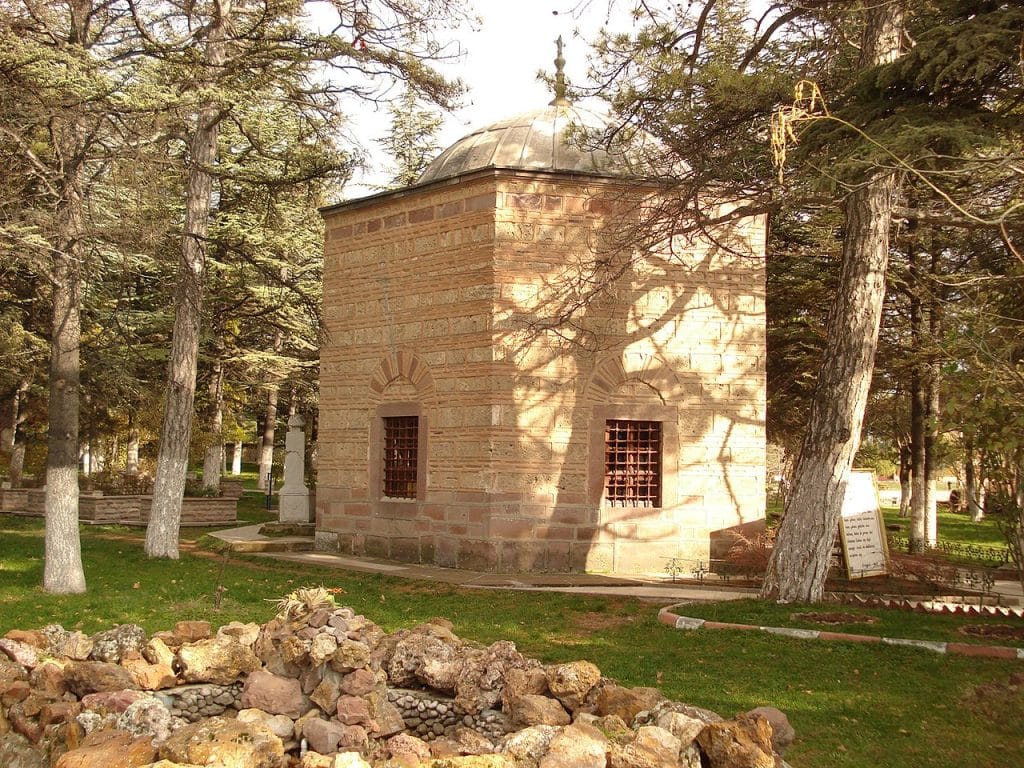

Due to the nomadic nature of Osman’s people and his emphasis on solidifying his territory, Osman’s rule was not credited with the construction of any elaborate architecture or art. It was not until 1333 CE during the rule of Osman’s son and successor Orhan I that the Hacı Özbek Mosque, the first building credited to the Ottomans, was built in İznik. In contrast to his father’s reign, Orhan would also oversee the gradual shift of his population from a nomadic way of life to a more settled life in the city.

Osman’s administration drew heavily on the Seljuk model, adopting their methods of warfare, emphasis on tribal relations, clothing, and even an insignia purportedly gifted to him by a Seljuk Sultan. He used the techniques of the Seljuks to great effect, possibly owing his success and battle prowess against the Byzantines to them.

Like his predecessors, the Seljuks, Osman, and his subjects belonged to the Sunni branch of Islam. However, beginning in the 12th century CE, a new school of Islamic thought called Sufism emerged. Much like the monks of Europe who devoted themselves to worship and spiritual development in monasteries, Sufis too held retreats in their lodges and engaged in religious enrichment activities such as dhikr. They also held an affinity towards literature and poetry and were responsible for many famous works published in the Ottoman Empire. Sufis and Sufism played an integral role in the court of Ottoman Sultans; starting with Sheikh Edebali’s relationship with Osman in the 13th century CE, the school of thought would continue to influence Ottoman policies for centuries to come.

After his death c. 1323 CE, Osman was buried in his hometown of Söğüt alongside his father, Ertuğrul. He remained buried there until Orhan reinterred them to Bursa, the city he named the new Ottoman capital following its capture in 1337 CE. Osman’s legacy survived long after his death. His successors would build upon the foundations of his achievements. Taking what was once a humble area of pasture land and small settlements inhabited by nomads, and transforming it into a mighty empire. While Osman himself did not have any grand accomplishments or glorious tales attributed to him as his successors would, his memory would live on as the name of his empire.