The Forgotten Women Philosophers of Anatolia

How women philosophers from Anatolia shaped intellectual traditions despite historical erasure

When we think of ancient philosophers, figures like Socrates, Plato or Aristotle dominate the narrative, their contributions immortalized in texts and teachings. However, history has largely ignored the voices of the women philosophers who shaped philosophical thought alongside them.

Women philosophers were active participants in the intellectual traditions of antiquity, serving as teachers, thinkers and leaders in various philosophical schools. Yet, their contributions were often erased or diminished, their names surviving only through fragmented accounts or the writings of their male contemporaries.

When did women’s history start getting erased?

The erasure of women’s history became more pronounced as Christianity rose to prominence and patriarchal norms solidified.

- Scholars have uncovered evidence that women served as clergy—deacons, priests and even bishops—in early Christian communities, holding equal roles to men in spiritual leadership

- However, by the fourth century, church councils systematically excluded women from leadership and intellectual spaces, relegating them to convents or private roles

- These acts were part of a broader historical trend of marginalizing women’s voices, erasing their active participation in intellectual and public life

Despite this, women’s contributions persisted and survived, particularly in regions like Anatolia—modern-day Türkiye.

As a crossroads of civilizations, Anatolia was a fertile ground for philosophical thought, blending Greek, Roman, and early Christian influences.

- It was here that women philosophers such as Artemisia I of Caria, Aspasia of Miletus, and Sosipatra of Ephesus flourished, leaving an indelible mark on the intellectual traditions of their time

Though often overshadowed, their legacies offer a glimpse into a world where women were not just participants but leaders in shaping philosophical and cultural thought.

So, let’s explore the lives and ideas of three remarkable women philosophers from Anatolia, modern-day Türkiye.

Artemisia I of Caria: Warrior queen who defied gender norms in ancient world

Artemisia I of Caria (fl. 480 BCE) is a remarkable figure in ancient history—a queen, naval commander, and trusted advisor to King Xerxes of Persia during the Greco-Persian Wars.

Although primarily known as a naval commander, Artemisia I of Caria’s bold strategies and political acumen offer parallels to the intellectual achievements of women philosophers.

As the ruler of Halicarnassus (modern-day Bodrum, Türkiye) and its surrounding territories, Artemisia’s strategic acumen and courage defied the expectations of her time, earning her a unique place in the annals of Greek and Persian history.

Warrior queen Artemisia’s early life, rise to power

Artemisia, named after the goddess Artemis, was born around 520 B.C.E in Halicarnassus, a Carian city that was part of the Persian Empire.

- Her father, Lygdamis I, ruled as the satrap (governor) of Caria, and her mother was of Cretan origin.

- Artemisia likely received an education that prepared her for leadership, a rarity for women in her era.

- She assumed power after the death of her husband, whose name has been lost to history, becoming the regent for her young son, Pisindelis.

- Her rule extended over Halicarnassus and the nearby islands of Cos, Calymnos, and Nisyrus, territories she would later bring into the Persian fold during Xerxes’ campaign against Greece.

Commanding Xerxes’ fleet: Artemisia at Salamis

Artemisia’s most famous military exploits occurred during Xerxes’ invasion of Greece (480–479 BCE). Herodotus, the historian and fellow Carian, provides much of what we know about her role in the conflict.

As the only female commander in Xerxes’ massive navy, Artemisia led 5 ships, reputed to be among the best in the fleet, during the naval engagements at Artemisium and Salamis.

- Battle of Artemisium (480 BCE):

Artemisia’s fleet participated in the three-day skirmish alongside the rest of Xerxes’ forces. Although the battle was tactically inconclusive, it allowed the Persian navy to regroup after the Greek withdrawal. - Battle of Salamis (480 BCE):

Xerxes sought the advice of his commanders regarding whether to engage the Greeks at sea. While the majority advocated for a naval battle, Artemisia stood out as the sole dissenting voice.

Herodotus recounts her reasoning in vivid detail: she advised Xerxes to avoid a naval confrontation, warning that the Persian fleet, composed of Egyptians, Cypriots, Cilicians, and Pamphylians, lacked the skill and discipline needed to counter the superior Greek navy.

Artemisia argued that Xerxes had already achieved his primary goal by capturing Athens and burning it to the ground. She recommended maintaining the fleet near the shore and focusing on a land campaign in the Peloponnese, predicting that the Greeks would eventually disband due to a lack of resources.

Her blunt assessment of the Persian navy’s inferiority, likening it to the disparity between “women and men,” was bold and demonstrated her keen understanding of the strategic weaknesses of Xerxes’ forces. Despite appreciating her candor, Xerxes chose to follow the majority opinion, resulting in one of the greatest defeats of his campaign.

Greeks enraged by a woman’s presence on the battlefield

Artemisia’s presence on the battlefield was an affront to Greek cultural norms, where women were not only excluded from military roles and political power but from all social spaces.

- Her competence and boldness not only challenged these expectations but also intensified the Greeks’ humiliation, as their enemies were led in part by a woman who outmaneuvered them both strategically and tactically.

- Her reputation as a formidable commander was such that the Greeks placed a bounty of 10,000 drachmas on her capture, a testament to how seriously they regarded her threat.

- Despite their disdain, no one succeeded in claiming the reward, as Artemisia outmaneuvered her opponents both strategically and tactically.

Herodotus observes that the Greeks’ disdain stemmed not only from her allegiance to Persia but also from her exceptional skill, which challenged their expectations. Her strategic acumen and ability to outmaneuver Greek forces were seen as a threat, adding to their humiliation when she evaded capture at Salamis.

Her performance at the Battle of Salamis—where she outwitted an Athenian ship by ramming an allied vessel to escape pursuit—solidified her reputation for bravery and ingenuity. Ironically, her calculated move not only saved her life but also earned Xerxes’ praise. Observing the maneuver from his vantage point, Xerxes famously declared, “My men have become women, and my women, men!”

Advisor to Xerxes: Strategic wisdom amid defeat

Despite the Persian loss at Salamis, Xerxes continued to value Artemisia’s counsel. After the battle, she advised him to retreat and leave his general Mardonius in charge of the campaign, reasoning that Xerxes’ survival and the preservation of the Persian Empire were paramount. Xerxes heeded her advice, withdrawing from Asia, while Mardonius remained in Greece with a reduced force.

As a reward for her service, Xerxes entrusted Artemisia with the care of his illegitimate sons, whom she escorted to safety in Ephesus. This act reflects the trust and respect she commanded in the Persian court.

Artemisia’s exploits earned her both admiration and vilification.

- Greek sources, such as Herodotus, highlight her courage and strategic brilliance.

- Others, like the playwright Aristophanes, used her as a symbol of audacious female power, likening her to the Amazons.

- Later writers, including the Macedonian historian Polyaenus, expanded her legend, though some accounts, such as the romantic tale of her unrequited love for a prince named Dardanus, lack historical corroboration.

Archaeological evidence also hints at her enduring legacy. An alabaster jar inscribed with Xerxes’ name was discovered in the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, possibly linking her lineage to later rulers of Caria.

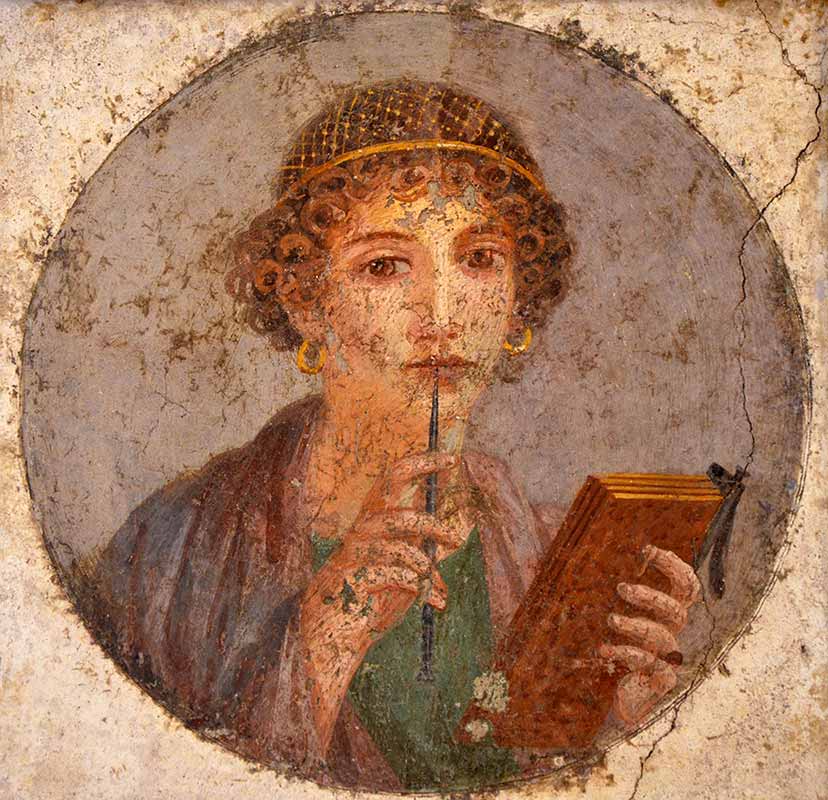

Aspasia of Miletus: Remarkable female philosopher who defied Athens’ taboos

Aspasia of Miletus (c. 470–400 BCE) emerged as one of the most remarkable women of antiquity, defying the gender restrictions of Classical Athens.

Born in the Ionian city of Miletus, near the modern village of Balat in Aydin Province, Türkiye, Aspasia likely received an education uncommon for women of her time.

Her birthplace was a hub of intellectual activity credited with producing early philosophers such as Thales and Anaximander. Thus, it may have played a pivotal role in shaping her intellectual abilities.

After moving to Athens around 450 BCE, Aspasia lived as a “metic” — a foreign resident of Athens. While this status excluded her from certain rights, it freed her from many of the constraints imposed on Athenian women. This allowed her to engage freely with the city’s intellectual elite, establishing herself as a philosopher, teacher, and conversationalist of great renown.

Aspasia and Pericles: The intellectual partnership that shaped Athens, democracy

Aspasia is perhaps best known as the lifelong partner of Pericles, who is credited for the establishment of democracy in Athens during its Golden Age.

Although Athenian laws forbade marriage between citizens and foreigners, Pericles openly lived with Aspasia, displaying his affection for her in ways that scandalized many Athenians. She bore him a son, Pericles the Younger, who was legitimized after Pericles overturned his own restrictive citizenship law.

- Ancient sources suggest that Aspasia’s influence extended beyond their personal relationship.

- Plutarch credited her with advising Pericles on political matters, describing her as a woman of rare wisdom.

- However, her visibility and intellect also made her a target of satire.

- Critics accused her of meddling in politics, with the playwright Aristophanes comically claiming she provoked wars to benefit her native Miletus.

Aspasia’s life epitomized the challenges and triumphs faced by women philosophers in a male-dominated society. Her contributions to rhetoric and practical wisdom align her with the broader tradition of women philosophers who engaged deeply with the intellectual currents of their time.

Socrates’ overlooked female teacher Aspasia: Pioneer of rhetoric in Classical Greece

Aspasia’s reputation as a teacher and philosopher is highlighted by her association with Socrates and other prominent intellectuals of her time.

- Plato’s Menexenus portrays her as Socrates’ instructor in rhetoric, a rare acknowledgment of a woman’s intellectual authority in the male-dominated world of philosophy

Her rhetorical prowess and ability to construct persuasive arguments are reflected in anecdotes and fragments from Socratic students and philosophers.

Below are 3 of the most significant records regarding her influence:

- Plato:

- In his satirical dialogue Menexenus, Plato credits Aspasia with teaching Socrates rhetoric and composing the famous Funeral Oration delivered by Pericles.

- While the dialogue is tongue-in-cheek, it reflects Aspasia’s reputation as an eloquent speaker and rhetorician.

- Aspasia is thought to have inspired Plato’s character Diotima in Symposium. Like Aspasia, Diotima instructs Socrates and discusses profound philosophical ideas, including the nature of love.

- Aeschines of Sphettus:

- Aeschines, a student of Socrates, wrote a dialogue titled Aspasia, though only fragments of it survive

- In one notable excerpt, Aspasia counsels Xenophon and his wife on marital harmony. Using philosophical reasoning, she advises the couple to focus on mutual self-improvement to achieve a successful relationship.

- This depiction showcases Aspasia’s ability to blend philosophical principles with practical wisdom, making her teachings relevant to daily life

- Xenophon:

- Xenophon, another follower of Socrates, referenced Aspasia’s expertise in interpersonal relationships and household management

- In his works, Memorabilia and Oeconomicus, Xenophon mentions Aspasia as a source of insight, particularly on fostering healthy partnerships and managing households

- This acknowledgment reflects her influence on both private and public spheres of Athenian life

Aspasia’s ability to teach and inspire prominent thinkers such as Plato, Aeschines, and Xenophon demonstrates her unparalleled intellectual presence in Classical Greece. Her contributions to philosophy, particularly in rhetoric and practical wisdom, earned her a lasting place in intellectual history.

Women philosophers in Athens: Aspasia’s independence impacted her image

Aspasia’s prominence in Athenian society was polarizing.

- While she was admired for her intellect and wit, she was also vilified in contemporary comedy and literature

- Aristophanes and other playwrights painted her as a scheming courtesan, perpetuating stereotypes about women who operated outside traditional roles

- However, serious writers, including Xenophon and Plato, offered a more nuanced portrayal, acknowledging her as a teacher and thinker

Aspasia also hosted what modern scholars describe as a salon, where Athens’ intellectual and artistic elite gathered to discuss philosophy, politics, and art.

This gathering space likely amplified her influence on the cultural and intellectual life of Athens, even as it invited criticism.

Though no works attributed to Aspasia have survived, her intellectual contributions are evident in the writings of her contemporaries. Modern scholars have revisited her legacy, portraying her as a philosopher, teacher, and proto-feminist who challenged the restrictive norms of her time.

Sosipatra of Ephesus: Clairvoyant philosopher, mystic of late antiquity

Sosipatra of Ephesus (fl. 4th century CE) stands out as one of the most enigmatic and fascinating figures of late antiquity—a Neoplatonic philosopher, mystic, and teacher whose life intertwined divine wisdom, clairvoyance, and intellectual rigor.

Her story, preserved in Eunapius’s Lives of the Sophists, shows a woman whose extraordinary abilities and philosophical acumen earned her respect and reverence in a male-dominated intellectual world.

A prodigious upbringing guided by Chaldean wisdom

Born into a wealthy family near Ephesus in Asia Minor, Sosipatra’s early years were marked by an extraordinary encounter. According to Eunapius, her father employed 2 mysterious men to oversee the family estate’s vineyards.

These men, believed to be “gods in disguise” or initiates of Chaldean wisdom, transformed the estate into a flourishing haven while imparting esoteric knowledge to the young Sosipatra. For 5 years, she studied under their tutelage, mastering ancient Chaldean traditions, theurgy, and clairvoyant abilities.

Upon her father’s return, he found a transformed daughter—radiantly wise and capable of recounting his experiences in his absence through her psychic powers. Her tutors, having fulfilled their task, vanished mysteriously, leaving Sosipatra equipped with profound spiritual and philosophical insight.

Sosipatra of Ephesus’ philosophical prominence, marriage

Sosipatra married Eustathius of Cappadocia, an orator and diplomat closely associated with the Neoplatonic philosopher Aedesius.

Despite Eustathius’ intellectual stature, Eunapius emphasizes that Sosipatra surpassed her husband in wisdom, beauty, and spiritual abilities. Together, they had 3 sons, including Antoninus, who later became a philosopher and mystic known for his prophetic visions.

Following Eustathius’ death, Sosipatra relocated to Pergamon, where she collaborated with Aedesius to establish a philosophical school. While Aedesius attracted a broader audience, Sosipatra’s teachings were reserved for an advanced inner circle of students, reflecting the profound respect she commanded as one of the most revered women philosophers of her era.

Among her students was Maximus of Ephesus, who would later serve as the tutor of Emperor Julian, reflecting the enduring influence of her intellectual legacy.

Sosipatra of Ephesus: Life marked by mystical encounters, psychic abilities

Sosipatra’s life, as narrated by Eunapius, abounds with tales of her extraordinary abilities:

- Clairvoyance: Sosipatra was renowned for her ability to perceive events across time and space. On one occasion, she accurately described a carriage accident involving her relative Philometor while it was happening miles away.

- Prophetic wisdom: She was revered for her insights into the past, present, and future. Her predictions, such as the fate of her family and the course of events surrounding her philosophical endeavors, consistently came true.

- The magical intervention of Maximus: When Philometor, infatuated with Sosipatra, used magic to compel her affections, she confided in Maximus, who countered the spell. Sosipatra later forgave Philometor, admiring his audacity and acknowledging the depth of his feelings.

Eunapius’ portrayal and the question of historicity

Sosipatra’s portrayal in Eunapius’ Lives of the Sophists reflects both admiration and the author’s intent to elevate pagan intellectualism in a time of Christian ascendancy.

- Her life is depicted as a counterpoint to Christian hagiographies, emphasizing her divine attributes, independence, and intellectual authority.

- While some scholars argue that Eunapius’ account incorporates elements of folklore and exaggeration, Sosipatra’s connections to historical figures like Aedesius and Maximus, and her role in fourth-century Neoplatonism, affirm her historical plausibility.

- Modern scholars, such as Maria Dzielska, suggest that the lack of broader references to Sosipatra may result from deliberate erasure (damnatio memoriae) of pagan figures in the Christianized Roman Empire.

Sosipatra’s contributions to philosophy and mysticism remain significant:

- Her integration of Neoplatonic philosophy with Chaldean theurgy bridged intellectual and spiritual realms, reflecting the synthesis of late antique thought.

- Her status as a woman philosopher and teacher challenged societal norms, inspiring admiration and reverence among her contemporaries.

- Despite the loss of her writings, her life, as recorded by Eunapius, continues to intrigue scholars and serves as a testament to the enduring legacy of women in philosophy.

In the words of Eunapius, Sosipatra was not just a philosopher but a “divine woman,” embodying wisdom, mysticism, and intellectual prowess in an age of profound cultural and religious transformation.

The lives of Artemisia, Aspasia, Sosipatra, and other women philosophers from ancient Anatolia reveal the significant yet often overlooked contributions of women to intellectual traditions.

Despite historical efforts to marginalize their roles, their ideas and achievements continue to offer valuable insights into the richness of philosophical thought.