The Message: Exploring the Birth of Islam in a Cinematic Masterpiece

Discover how The Message brings the story of Prophet Muhammad and early Islam to life with powerful performances and timeless messages.

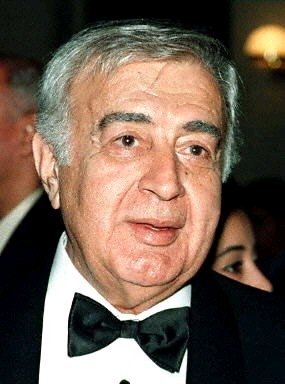

Moustapha Akkad, the director of “The Message” – a quality, landmark production describing the history of Islam – died in November 2005. He was tragically killed in an al-Qaida terror attack in Amman, Jordan. Let’s reflect on the “messages” of the film of the veteran director, who passed away exactly 15 years ago.

Paternal heirloom

The driving force that pushed the director to create “The Message” was a sense of loyalty to his family. Akkad was born in 1930, as the son of a customs officer from Aleppo. When Akkad turned 18, he informed his father of his dream to move to the U.S. and become a Hollywood director – a pipe dream in 1940s Aleppo. However, Akkad’s father listened and allowed his son to pursue his passion. Soon, the 18-year-old was saying goodbye to his family at the Damascus airport, where his father handed him $200 he had saved and a Quran, and said: “All I can do for you is to give you these. From now on, I may or may not see you again. Never forget, my prayers are with you.”

Akkad said this was the first step in his 50-year adventure in cinema, noting: “Hadn’t my father acted like this back in those days, there would have been neither ‘The Message’ nor ‘Lion of the Desert.’”

First steps

When Akkad arrived in Los Angeles with just $200 in his pocket, a pocket-size Quran, and poor English, the world was entering a new order after World War II. Despite the challenges he faced, Akkad managed to study at the University of California. Although he was poor, he achieved academic success. During his time at the university, the young filmmaker met Sam Peckinpah, a legendary director from the same school.

They collaborated for a long time on a film about the Algerian liberation struggle, but financial problems prevented its completion. This project marked Akkad’s first directorial experience in the United States.

The real adventure for Akkad began in 1974. He believed that global crises stemmed from a failure to understand the universal messages of the Prophet Muhammad. To address this, Akkad decided to explore the prophet’s life to convey his teachings. He began working on his groundbreaking project, “The Message.” In an interview with The Washington Post, he explained, “Being a Muslim myself who lived in the West, I felt that it was my obligation, my duty, to tell the truth about Islam.”

Success against all odds

He traveled to Saudi Arabia and on to Morocco, where he received positive feedback when pitching his project, and left with the support of the two wealthy Islamic states. He made his first deal with Mexican-American actor Anthony Quinn. Quinn’s acceptance of the role of Hamza, the Prophet Muhammad’s uncle, convinced many other actors who had been hesitant to take on roles. The project featured celebrities like Irene Papas, Michael Ansara, Andre Morell, Michael Forest and Johnny Sekka.

The film’s director of cinematography was Jack Hildyard, the Oscar-winning director of “The Bridge on the River Kwai” and the script was written by Harry Craig under the supervision of Egyptian Islamic historian Tawfiq al-Hakim. Maurice Jarre, a veteran Oscar laureate, composed the score – becoming so focused on the project that he composed the score alone in the desert.

Akkad attempted to shoot an Arabic version of the film, titled “Al-Risalah” and put together a cast of prominent Arab actors of the time. A team of 500 people began preparations to shoot scenes for both versions of the film in the Moroccan desert when Saudi Arabia and Morocco announced the withdrawal of their support. The Moroccan government even warned Akkad to “leave the country as soon as possible.”

Akkad took Quinn and went to Libya, where he managed to arrange a meeting with Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi. Gadhafi told him that he would solve all of his problems and that he and his team could shoot the film in Libya. Finally, the film set was put up in the capital Tripoli, with Gadhafi being so supportive of the project he even sent special air conditioners, worried that the film crew was suffering in the desert heat.

Fair Christian king

“The Message” begins with the Prophet Muhammad sending letters to rulers of the Eastern Roman Empire, Persia, and Egypt, inviting them to believe in one God. The film then portrays pre-Islamic Mecca, where the Kaaba lies desecrated.

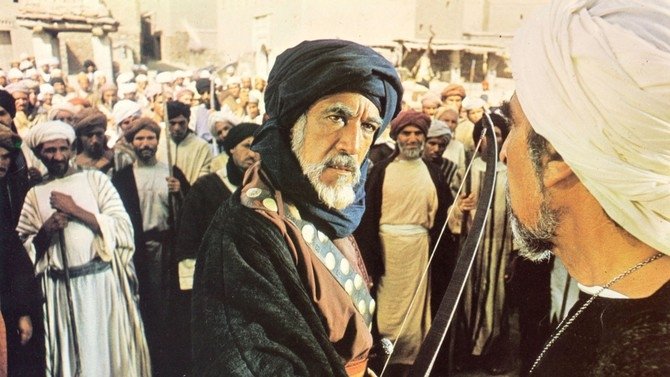

Damien Thomas, as Zayd, delivers the first revelation: “Read!” As the message spreads, Mecca’s elites offer concessions to halt Islam’s growth. When Abu Talib, played by Michael Morell, relays their proposals, the prophet rejects them, declaring, “Were they to put the sun in my right hand and the moon in my left, I would not renounce my message.”

Hostility escalates, leading to attacks on the prophet and his followers. Anthony Quinn, as Hamza, confronts Abu Jahl (Martin Benson) after an insult to the prophet, silencing him with a blow and challenging the oppressors, marking a turning point in the resistance.

Although powerful figures such as Abu Bakr, Hamza, and Omar embraced Islam, the era remained marked by the strong oppressing the weak. As a result, Muslim slaves and vulnerable families endured severe torture. One of the most dramatic scenes in the film depicts Ammar ibn Yasir and his family suffering such atrocities.

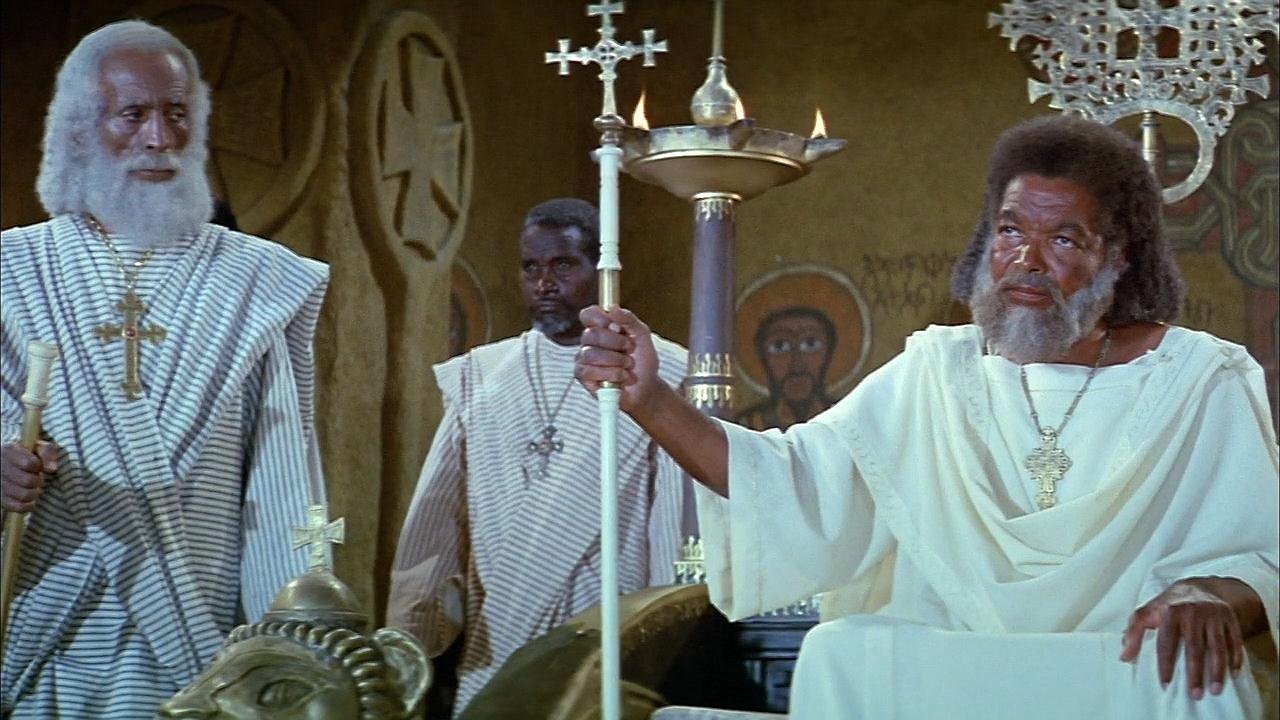

In response to the persecution, the prophet advises the oppressed to seek refuge with the fair Christian King al-Najashi in Abyssinia, stating, “No human is wronged in his country.” The king welcomes the Muslim emigrants and offers them shelter. The dialogue between the king and the prophet delivers Islam’s universal messages with remarkable eloquence.

‘The Message’ or ‘Al-Risalah’

Although the Arabic version of the film has exactly the same script and film set as its English counterpart, it had a different impact on the audience. In “The Message,” actors who literally impersonate the roles carry the audience along with the film emotionally. In “Al-Risalah,” the acting seems a little poorer, but this could be due to the exceptional performances in the English version, in comparison.

Unlike the English version, what makes the Arabic version notable is the use of Modern Standard Arabic. After all, the Quran is in Arabic and spread from Arabia. As you watch “Al-Risalah,” the literary flow of Arabic and the reading of the original verses makes the experience feel more rooted in reality.

The most striking shortcoming in the film’s overall script is the character development of those who later convert to Islam, whose descriptions do not do them justice and are misrepresented as evil figures. For instance, the character of Hind, played by Papas, actually becomes Muslim after the conquest of Mecca in real life. She even influences many women in Mecca to convert to Islam. Unfinished roles like Hind lead to a bias against real historical characters.

“The Message” still remains a cult production of cinematic history, both for its script and artistic quality. Akkad challenged Mussolini’s dictatorship in Italy with another masterpiece, “Lion of the Desert.” The veteran director had two other film projects he had planned to realize about Islamic history. The first, about the conquest of Istanbul and Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II, also known as Mehmed the Conqueror, and the other about Saladin, the Muslim conqueror of Jerusalem. He started working on the film “Saladin” and even made a deal with Scottish actor Sean Connery to play the lead role, but terrorism did not allow it.

From Early Islamic Struggles to Timeless Lessons

The Message isn’t just a film—it’s a profound journey through the trials and triumphs of the early Muslim community. To explore more about the rich history of Islam and its cultural heritage, visit OsmanOnline.me for engaging articles. For historical dramas and films that bring these stories to life, stream in full HD on OsmanOnline.live.